Going In to Go Out: A Friendship with Wynton Marsalis

Over the next two years, Wynton Marsalis will transition from his current roles at Jazz at Lincoln Center, as Managing and Artistic Director, to remain on the Board as an Advisor and a perpetual member, in his role as Founder. When I first met Wynton on Friday, August 6, 1993, after the “Battle Royale: Trumpets and Tenors” concert in which he jousted with fellow brass men Roy Hargrove, Nicholas Payton, and Wallace Roney, it was a dream come true. Ever since he began generating buzz in 1980 as a double threat in European concert music and American jazz, I had followed his career and hoped to one day cross paths with him.

He came on the scene right when my lifelong love and dedication to jazz took root in the late ‘70s. Wynton’s albums adorned the walls of my dorm at Hamilton College in the early to mid-‘80s, and his early work with Art Blakey inspired me to see him perform with “Buhaina” at Mikell’s in NYC. He was fearless on the bandstand and when speaking his mind about the state of jazz and music in general. The latter got him in hot water with the “liberal” jazz press and even with musicians of his and the previous generation who felt he hadn’t paid enough dues to warrant the publicity, pay, and platform to become a spokesman for jazz.

Yet for me, he was a breath of fresh air, validating my own obsession with straight-ahead, acoustic, swingin’ jazz. When he was featured on the cover of Time Magazine on October 22, 1990, I was thrilled to discover that he also loved basketball. So when, after the 1993 concert, he and other bandmates decided to play basketball a few blocks from the high-rise overlooking the Hudson where he lived, I wasn’t surprised. But I also wasn’t expecting to play basketball that night; I was wearing dress shoes. It had also rained earlier that day, so when I decided to play anyway, Wynton warned me: “Man, you better watch out and not bust your ass.”

I was careful, and Wynton could see that I had some game. After we returned to his apartment, where other musicians, friends, and lovely ladies were present, we rapped for several hours. So in the coming months, we played b-ball a few more times, both team and one-on-one. I just wish that when I envisioned one day meeting and playing basketball with him, I had imagined not just playing him, but beating him, too. But I could never best him on the court or in chess either. Nonetheless, what was most crucial was a budding friendship in which I could speak to him, man to man, about anything and everything, from music to family and relationships to literature and ideas.

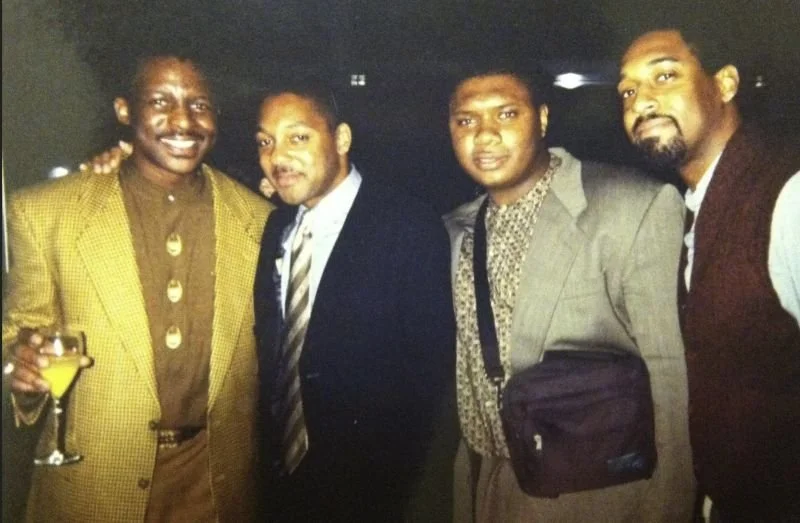

Herlin Riley, Wynton Marsalis, Wycliffe Gordon, and Greg Thomas

For instance, when I wrote Wynton a letter in the late 1990s, criticizing him for what I thought was a lack of respect toward Miles Davis, he called me. “First, thanks for taking the time to write and express yourself to me,” Wynton said. Then he told me about his relationship with Miles over the years and gave me an analogy. “If someone came to me, and really knew my music as well as I know Miles’ music, inside and out, and was able to critique my music in musical terms, it would mess me up. Man, what Miles began playing in the 1970s and 1980s cannot compare to his classic jazz recordings.”

Even though I still disagreed with some of his remarks about Miles back then, his appreciation of my passionate position and willingness to dialogue with me about it meant the world to me.

Representative Anecdotes

In truth, there are many other moments I treasure:

Wynton performing gratis at a graduation ceremony, at my request, for a middle school in Brooklyn that I worked at in the late ‘90s.

Before a JALC Orchestra rehearsal, handing me sheet music written in Duke Ellington’s own handwriting, and shortly thereafter advising me to, rather than complain about the lackluster work of some second-rate academic I was reading in graduate school, to “put your own shit out here.”

Watching Wynton, again in his apartment, with a group of young trumpeters hanging on his every word, but Wynton letting the music speak, playing a stunning number by Mahalia Jackson, followed by a Louis Armstrong cut with a similar majesty of soulful expression.

Visiting a bedridden Albert Murray in his Lenox Terrace apartment together, a year or so before Murray joined the ancestors.

My daughter Kaya going with me to Wynton’s abode several times when she was a pre-teen. On one occasion, I passed a blindfold test he gave me in front of her. He was playing acapella double-time choruses when, suddenly, he stopped and asked, “What song is that?” I said, “Come on, man: 'Giant Steps.’”

Bringing Kaya backstage at JALC a few years later, and Wynton eyeing her and declaring: “Man, she’s got it! We need to bring her here to intern!”

Running into Wynton on 57th and Broadway in 2012 and excitedly informing him that Kaya was admitted to Dartmouth as an undergraduate. He looked at me and matter-of-factly said, “What do you expect? She’s smart, man.”

Wynton, Kaya, and her Dad at a JALC rehearsal

Wynton’s Leadership Style

Over the years, I’ve also observed his approach to leadership. As I wrote several years ago for this newsletter:

Behind the scenes, Marsalis enacts the principles of collaborative, interdependent leadership by example. For instance, he shares arranging duties and distributes authority among the JALC Orchestra members. Although deeply influenced by Ellington’s style of leadership, in which Ellington (and his partner Billy Strayhorn) did all of the arranging and orchestrating, Marsalis circulates decision-making widely across the network of talent in the band….

Other band members serve as musical directors for JALCs' themed concerts, making decisions on the repertoire and which colleagues will handle the arranging. During the crucial days of rehearsal practice before a live concert, the arrangers of each song take the lead in determining tempo, phrasing, and solo order. Any band member can speak up and make suggestions during rehearsal.

I was present at a rehearsal in which a member of the saxophone section served as the Musical Director. In between numbers, he turned back to ask Wynton what he thought about a musical matter. Wynton’s response? “What do you think?”

Wynton’s Daily Prayer

I began my liner notes for the two-CD set of compositions from over his career, from the Sony Masterworks series, The Music of America, like this: “Yes and Love. These two words summon the affirmation and arc of intention, and the meaning and values at the core of Wynton Marsalis’s oeuvre, a small sample of which is contained on this two-disc set.” At the arc of their soulful core, the affirmation of life signaled by Yes and the ineffable transcendence of the word Love is spiritual.

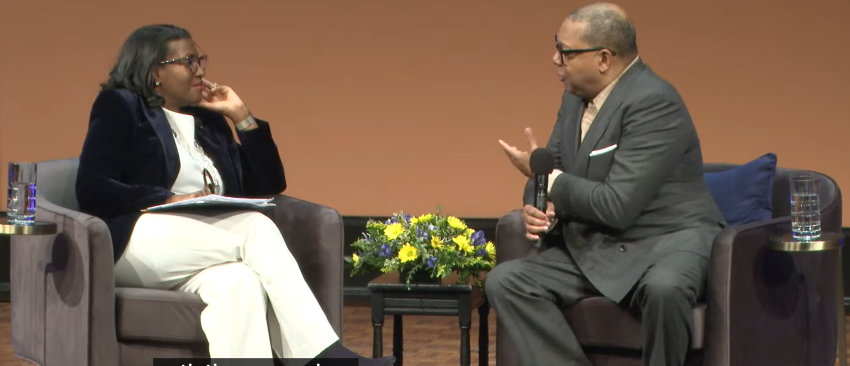

Dean Celeste Watkins-Hayes and Wynton in conversation

On February 4, 2026, Wynton joined the University of Michigan’s Ford School Dean Celeste Watkins-Hayes for a public conversation reflecting on America at 250, the role of music in our culture and society, and the ways artists help shape our future. The dean asked Wynton a penetrating question that framed his career in music over the decades, as reflecting the “sensibility of your soul.” In part of his response to her call, he said:

“The soul is all there is to it. I say a prayer every morning:

Lord, from you all things, though we are many, in life and death, we are truly one. Just the calling of your name releases us to perceive the oneness of all in all... For you have given us through your word, the divine thought, and the divine thought is the divine manifestation, is holy action. Mighty is the healing of thy name, oh Most High. May we shout it out in kingdoms, earthly and divine.

“The bass line of our lives is the soul. As you go [inside] a person, there’s less and less differentiation. If we went one level below, to our skeletons and cartilage, you wouldn’t know who is who. But say you could tell from the size [of the person]. Then we went to the organs, and then the tissues, and into the vessels. Now we’re at the cellular level, [the] molecular level. Then we get the spirit, and it’s one. It’s designed to be that way. That’s why you go in to go out. And we know this because when you’re born, you go in, and when you die, you go out. And all through your life you’re going in and out [breathing]. And all the universes are doing that.

“It seems like mysticism, but it’s not. It’s fundamental.”