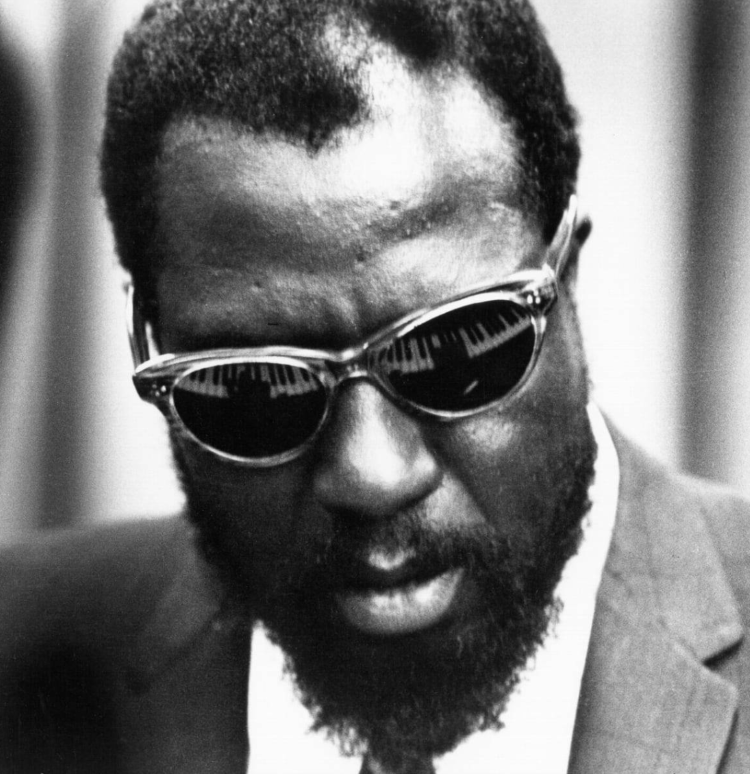

The Sorcerer: Thelonious Monk and the Art of Positive Deviance

A genius is the one most like himself.

—Thelonious Monk

In the very first lines of the first chapter of the great sociologist Orlando Patterson’s 1977 book Ethnic Chauvinism, he identifies two great forces that underlie the progress of human culture. “One pulls us toward the bosom of the group; the other pushes us toward the creation of ourselves as separate and distinct individual beings.”

The archetype of the latter force was the mythic figure of the sorcerer, who exhibited prototypical “deviant individuality” in contrast to “conforming individuality,” in which conformists seek to further the “ends of the group by becoming as near as possible like every other member.” In Patterson’s telling, by expressing deviant individuality, the sorcerer symbolically became the “original individualist and intellectual,” even before the development of individuality in classical Greek philosophy, the Renaissance, and the Enlightenment era.

For him, creativity becomes an end in itself and a means for the promotion not of the collectivity, nor of some abstract entity called the group or tradition, but of his own ends and the ends of other individuals… he enjoys the act of creation for its own sake… he places the interest of his own individuality and of those with whom he comes in contact above that of the group…

—Orlando Patterson, Ethnic Chauvinism: The Reactionary Impulse

From Deviant Individuality to Positive Deviance

I recently read about the contemporary idea of “positive deviants” in the book One Mission: How Leaders Build a Team of Teams by Chris Fussell. He frames positive deviance as “intentional behaviors that depart from the norms of a referent group in honorable ways.”

The concept is simple: look for outliers who succeed against all odds. ‘Positive deviance is founded on the premise that at least one person in a community, working with the same resources as everyone else, has already licked the problem that confounds others,’ often through unconventional means that their peers fail to recognize. Importantly, this individual’s outcome ‘deviates in a positive way from the norm.’

Monk’s Sorcery and Positive Deviance

Thelonious Monk’s innovative approach to jazz composition aligns closely with the concept of “positive deviance” as used in social science: he achieved exceptional, groundbreaking results by deviating from the prevailing norms of the pre-bebop era of the music, just as exiled, mythic sorcerers parlayed “deviant individuality” back in the day. This connection is apparent both in Monk’s stylistic choices and in broader patterns of innovation attributed to honorable positive deviants. Monk’s style—his rhythmic displacement, melodic innovation, percussive harmonies, and embrace of what to untrained ears sounded like “errors”—embodied the positive deviant’s journey from outlier to exemplar. His legacy demonstrates that bold nonconformity, sustained by internal vision and discipline, can extend the tradition by being most true to oneself.

Any artist is always carrying on an ongoing dialogue with the form that he’s practicing in … [E]ach time he adds something, each time he comes up with something valid, it alters the total emotional scale of that form.

—Albert Murray, in conversation with Wynton Marsalis

A key practice through which Monk achieved this sui generis level of genius, which reinforced the fundamental imperatives of jazz while altering the emotional scale of the music, was syncopation. In our Jazz Leadership Project workshops, our trio performs Monk’s “Evidence” to demonstrate the practice. Why? Monk's approach in "Evidence" was a masterclass in syncopation, achieved through metric displacement, offbeat hits (accents), and angular, chromatic motifs that destabilized and yet energized the memorable melody based on the standard “Just You, Just Me.”

Here's an exemplary version of “Evidence” from a live performance in Brussels in 1963.

Syncopation as Wise Leadership Practice

Syncopation has a quality totally unique to any other construct in the universe… syncopation allows you to retain your own individuality and way of playing rhythm and still maintain a group effort. Syncopation is the glue that holds a performing group together.

—Hal Galper

. . . true jazz is an art of individual assertion within and against the group. Each true jazz moment … springs from a contest in which each artist challenges all the rest; each solo flight, or improvisation, represents...a definition of his identity: as individual, as member of the collectivity, and as a link in the chain of tradition. (Emphasis added.)

—Ralph Ellison, “The Charlie Christian Story”

The jazz approach to syncopation resolves the tension between the individual and the group, a dynamic that has been present since early human cultural development and remains relevant today. Via syncopation, disruption can be framed not as a problem to be solved, but as a potential resource for growth and evolution. By recognizing the creative power in strategic interruption of expected patterns, jazz-inspired leadership transforms what might otherwise become stagnant predictability into engaging development that piques cognitive interest and ensures forward momentum.

This isn’t about romantic disruption in an adolescent fashion, bucking norms just for the heck of it. Rather, this syncopated angle on leadership offers sophisticated ways to introduce suitable discontinuity, catalyzing growth and innovation through the sweet sound and feel of surprise. Monk deliberately introduced syncopative devices not to abandon structure, but to enrich it, to extend and elaborate it, through creative tension. Similarly, leaders can develop approaches that maintain coherence while introducing strategic disruptions to prevent stagnation and facilitate adaptation.

For your own leadership journey, consider these reflective questions:

Where might strategic disruption create possibilities unavailable through maintaining current patterns, regardless of their apparent efficiency or comfort?

What aspects of your leadership presence become challenged during unexpected developments? How might you strengthen your capacity to remain centered and responsive despite uncertainty?

What elements of organizational capacity most need development to support sustained adaptation—learning systems, cultural resilience, or structural flexibility?

Where do you notice resistance to strategic disruption—either in yourself or your organization? What underlying assumptions or values might create this resistance, and how might reframing disruption as a potential resource help transform this relationship with the unexpected?

The answers to these questions can help shape your individual approach to leadership through syncopation and embolden your unique path for introducing strategic disruption. Like Monk, your leadership journey can be an opportunity to transform complacency into dynamic development, fostering a delicious deviancy, through the creative power of embracing the unexpected.