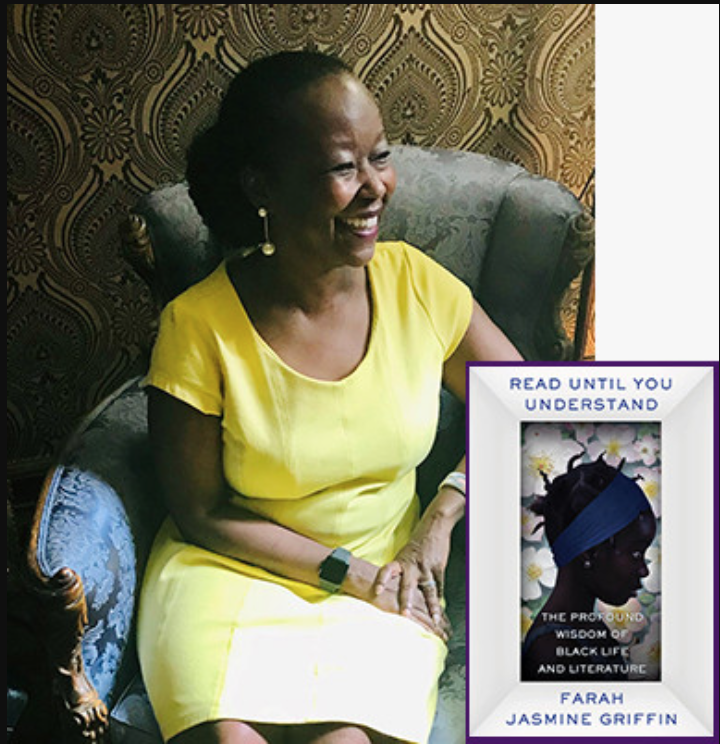

Transformative Love: Farah Jasmine Griffin’s “Read Until You Understand”

Although the title of Farah Jasmine Griffin’s latest book begins with the word “read,” I did more; I also listened. After reading the hard copy first edition, I supplemented prep for this book review by waking up in the middle of the night several times last week and attaching my Bluetooth ear buds. In bed next to Jewel, I luxuriated in images and sounds and memories familiar yet different. While traveling to and from visiting my mom on Staten Island this weekend, I finished the journey through the ten chapters again, hearing Griffin’s words in her own voice as an audiobook on Audible, her honey-rich contralto narrating her personal story of growing up in Philadelphia and providing insights and lessons from the Black American writers she teaches as a Professor of English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University, from books that are important to her for personal reasons too.

From the intro, context:

This book begins with a girl and ends with grace. Along the way, through a combination of memoir and readings of African American literature, it touches upon the question of mercy, the elusive quest for justice, the prevalence of beauty, even in the presence of death, and throughout, hope in the face of despair.

Both the autobiographical reflections and my readings of the literature speak to the ideals and failures of the U.S. experiment with democracy. My goal in writing this book is to draw upon a lifetime of reading and almost thirty years of teaching African American literature to explore how, in addition to addressing concerns about democracy, perhaps even more than these, the works also speak to ideas and values that have concerned humanity since the beginning of time. Within these pages, I seek to share a series of valuable lessons learned from those who have sought to better a nation that depends upon, and yet too often despises, them. In the process, they have changed the world.

Dr. Griffin’s Read Until You Understand: The Profound Wisdom of Black Life and Literature is a lyrical meditation on what sustains the souls of Black folk amid grief and loss; how the joy of learning and reading transforms perception and therefore reality; and the way all from music and food to conversation and sewing and gardening allows a family—and, by extension, a community—to stitch together a quilt of shared meaning despite differences of occupation, style, religion, and in spite of the indifference (or worse) of an outside world where exploitation and inequality is a casual norm based on what Stanley Crouch called “the decoy of race.” In a masterful work of creative nonfiction, Griffin intersperses her own story with that of her family, her neighborhood and city, with the learnings garnered over the hundreds of years of our sojourn on these shores as told in narratives of literature and in headlines up to 2021.

Early in the work, she shares the devastating and unjust account of the loss of her father at the age of nine. A daddy and momma’s girl, Farah remembers her father’s love of bebop jazz, his storytelling, his agnosticism, his holding her by hand on trips to historic places in Philadelphia, his introducing her to the documents of the founding fathers and of “intellectual freedom fighters” such as “Toussaint Louverture, Nat Turner, Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, the Black Panther Party, and Angela Davis.”

The lessons learned from him and other family members, especially her mother and aunts, are woven throughout the work. Toni Morrison, who Griffin first read at thirteen, also holds a special place throughout. Although she had read other Black American women writers such as Nikki Giovanni, Lorraine Hansberry, Toni Cade, and Alice Walker before her, Morrison’s Sula opened a portal of understanding of herself and her community like no other.

Sula felt like the beginning of a new knowing. Here was a world in some ways familiar and in other ways completely different from the one I knew. Here was a language that sounded like the language the women around me spoke, but presented in a way so that I heard its imagery, its beauty, its rhythm. This was the beginning of the written word entering into my consciousness in the way that others imbibed the words of the Bible. From here on, more than any scribe of the Old or New Testament, Morrison would inform my understanding of my family, my history, and the nation that I called home. She would also shape my voice, my juvenile attempts to use language to describe the world around me.

Chapter 8, “Joy and Something Like Self-Determination,” is one of my favorites for its brief departure “from the world of books to the landscape of sound.” Although I was growing up in Brooklyn, NY during the time of this chapter’s focus, the 1970s, the artists and musical genres she relates were a shared national (to international) inheritance. The section on the significance of Stevie Wonder before and after his life-threatening car accident in 1973 is a precious memory of Stevie’s greatest period of stunning creative production. Central to this chapter is her family’s restaurant, a gathering place where you could find “gangsters and factory workers, politicians and entrepreneurs, Christians and Muslims—we all listened to and danced to and argued about and discussed the same music, while eating chicken and cheesesteaks—and, if my aunt felt like cooking on the weekend, ribs and chitlins too, although a bunch of folk didn’t touch that ‘swine.’”

We were a people.

Through the door of that restaurant, in walked us.

Transformative Love

My very favorite chapter is “The Transformative Potential of Love.” That’s because “love” is what I most associate with Professor Griffin, Farah, who mentions that word, that force of good, truth, and beauty in the second sentence of the first chapter, “Legacy, Love, Learning,” when recalling that her love of Black American history and literature began with her father.

If memory serves, I first encountered Farah at a meeting of the Jazz Study Group at Columbia University in the late 1990s. Bob O’Meally, her colleague there, asked me to join the group, which became the Center for Jazz Studies, when I was engaged in doctoral studies at NYU’s American Studies program.

Years later, at a regular spot in Harlem we’d meet to plan and conspire, I recounted to Greg Tate my admiration of Farah’s stance on the luminaries of our history. Greg looked at me and said: “You talking about love.” In my estimation, Farah didn’t either-or Booker T. and W.E.B. Du Bois or Martin and Malcolm, as if you had to choose one and distance yourself from the other. Rather, she took a both-and stance. She embraced them the way we accept family members even when we disagree with them.

Photos: Richard Conde

I had interviewed Farah for the National Jazz Museum in Harlem’s “Harlem Speaks” archival conversation series about fifteen years ago. She was as gracious and warm and beautiful as when I watched her on Avon Kirkland’s PBS documentary on Ralph Ellison, where she recalled that an evident quality in Ellison’s work is his “love of Black people.” She was capacious, creating a room with a view of our musical and literary legacies as representative gifts to the world. Also significant for me was her emphasis on the work of under-appreciated Black women artists in what became her book, Harlem Nocturne: Women Artists and Progressive Politics During World War II. In a panel at Harlem Stages at City College on the legacy of Mary Lou Williams, one of three figures of focus in that work, her love of Mary Lou’s legacy was palpable.

As host of the panel, I witnessed, backstage, her and the late, great pianist Geri Allen speaking privately. Watching their easy intimacy reminded me of the close, secretive conversations of women in my own family. When I recalled these moments for Greg Tate, we used Farah’s example of love to suffuse our friendly public debate where Greg reimagined Amiri Baraka’s position on the blues, and I recollected Ralph Ellison’s.

Carol Bash, Geri Allen, Farah Jasmine Griffin, and Greg Thomas at Harlem Stages discussing Mary Lou Williams.

James Baldwin and Morrison are the prime literary movers of “The Transformative Potential of Love” chapter, which begins by telling the tale of the love affair between Farah’s mother and father. The chapter concludes by Prof. Griffin, inspired by two sermons in Morrison’s Beloved, engaging in philosophical and spiritual inquiry:

Suppose what we call God is nothing more than a conception of human beings loving each other, treating each other with mutual respect? Suppose we create and live in something divine each time we act lovingly and respectfully toward each other? Suppose humans are the only vehicles and vessels of Grace and Love? This kind of love is the basis of justice. This love is the conduit of freedom. This love is power beyond wealth, greed, and physical might.

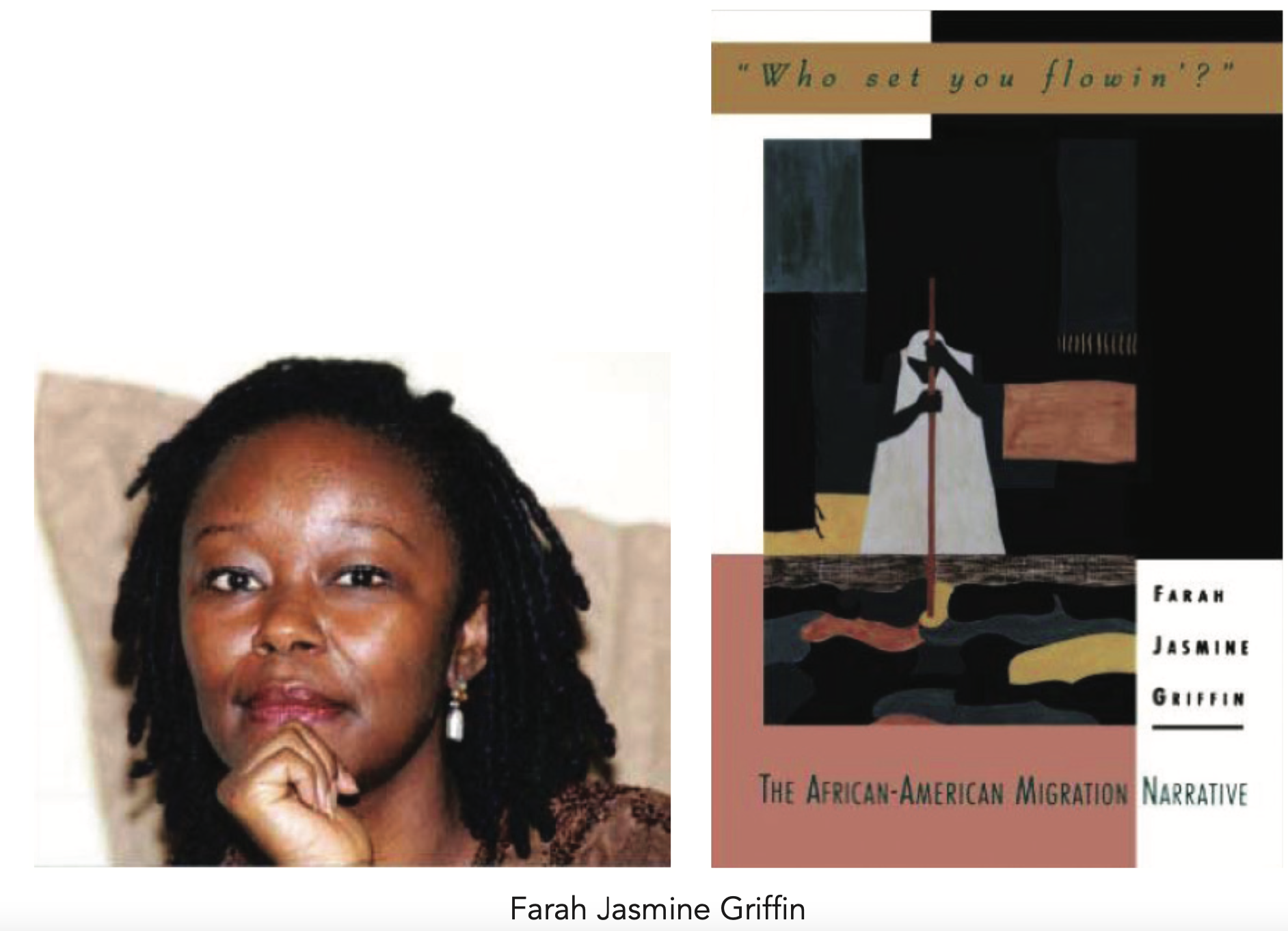

My only disappoint was no mention of Morrison’s Jazz in this work. Perhaps she felt she had covered that ground in the closing chapter of her first book, Who Set You to Flowin’?: The African American Migration Narrative. But this minor quibble is washed away by the love contained in this memoir and reading of Black American literature and history. If you’re inspired to read and listen to this timely meditation, you’ll understand too.