How Playing with Clark Terry Changed My Life

My last blog post, about my high school experience of jazz music taking over sports as my passion, were the very beginnings of a love affair. But music became my life-long mistress in college, where my dorm walls displayed the early recordings—both classical and jazz—by Wynton Marsalis as inspiration. At Hamilton College, my music minor included a survey of the history of Western music while playing in bands, small and large.

The soundtrack of my life still included R&B artists like Teddy Pendergrass and Luther Vandross. Yet my ears, heart and soul were centered on my love affair with bebop and other jazz styles, and legendary jazz artists such as:

Ella Fitgerald and Sarah Vaughan

Cannonball Adderley and Clifford Brown

John Coltrane and Miles Davis

Dave Brubeck and Paul Desmond

Carmen McRae, Betty Carter and Nancy Wilson

Benny Golson and Horace Silver

and Ben Webster and Harry “Sweets” Edison from an earlier generation of jazz masters.

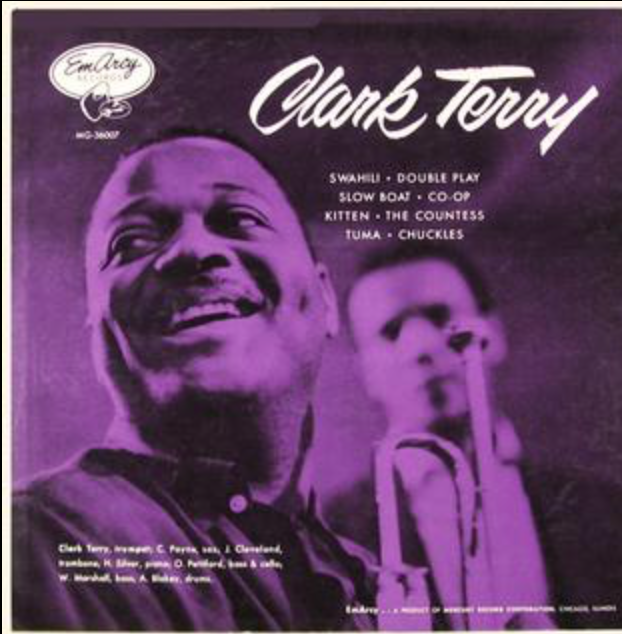

But it was there, at Hamilton College, that my life forever transformed, when I played with a bona fide jazz grandmaster junior year, Clark Terry, who would have been 100 today.

I’d travel from Staten Island to the school, located on a hill in a small town in central New York state, via Amtrak along the Hudson River. In early autumn and late spring, the Hudson displayed a stunning array of colors on the Palisade cliffs, which rose high along the water’s edge.

In fall, the cliffs would shimmer in shades of red, yellow, purple, and magenta. In the spring, various shades of green would blossom, rendering nature’s recovery from the chill and frost of winter. Hopping on at Penn Station, the train would let me off close to five hours later in Mohawk Valley.

I hosted a jazz radio show on the college station, WHCL, for all four years. I played jazz classics to the new music of the young lions from the birthplace of jazz, New Orleans, such as Wynton and Branford Marsalis, and Donald Harrison and Terence Blanchard.

Unlike high school, where I played second alto, in college I played first alto in the college’s big band, led by Don Cantwell. Mr. Cantwell was different from my high school music teachers, brass man Nathan Axel and woodwind wiz Mike DeBetta. Mr. DeBetta was Italian cool; Mr. Axel, rotund and jolly. Mr. Cantwell, who played hard-edged alto sax, had an absent-minded professor vibe, but would entrance me with stories about saxophonist J.R. Monterose, an upstate New York horn legend born in Utica, only a half hour from the college.

Unlike my beloved private sax teacher Caesar DiMauro, whose style evoked Lester Young and Zoot Sims, Mr. Cantwell was the one who in practice sessions demonstrated to me the way Charlie “Bird” Parker’s sound was distinct from Johnny Hodges and Benny Carter’s, and why, within the context of bebop.

My high school buddy Mason Ashe also matriculated to Hamilton, and, as with the Stage Band at Tottenville High, held down the guitar chair in the big band and smaller groups I played in on campus. One of those small groups was called Delta Bop, a name derived from most members of the band being brothers of the Delta Phi fraternity and living in the Bundy dormitory downhill from the main campus, as did I sophomore year. Cool drummer Joe Duffus, swingin’ with a cigarette hanging from his mouth, and gentle-souled Bill Dentzer, pianist and trumpeter, lived in Bundy, where we, bassist Paul McGowan, and pianist and clarinetist Jamie Rhind spent many hours listening to tunes and, as we used to say back then, gettin’ nice.

At the start of the spring semester of my junior year, Mr. Cantwell announced that the big band would play the music of the legendary trumpet man Clark Terry, with Terry himself performing with us.

OMG.

The date was April 17, 1984. Before meeting him, I did my research.

Turns out Quincy Jones was Clark Terry’s first student in 1946. Clark Terry was Miles Davis’s hero in St. Louis. Terry’s own apprenticeship took place on bandstands and in recording sessions with the orchestras of Count Basie and Duke Ellington.

To say I was scared to meet and perform with him would be an understatement.

After rehearsal, the day before the concert, band director Cantwell, Mr. Terry, a few select band members and I broke bread together at a quaint, cozy restaurant in the town of Clinton, even further downhill from campus. I was quiet and nervous. I couldn’t hide my sense of awe being in the presence of one of the greatest, most beloved jazz musicians and teachers in the world. Fortunately, Clark set me at ease by calling me by my first name, “Hey, what say, Gregory?” and making small talk.

The college’s chapel was located right in the middle of the bucolic, ivy-lined campus. That’s where the moment of truth took place. From November through March, the campus was white with snow, but on that special day, the scene was clean.

In that sacred sanctuary, the very next night, Clark and I played the melody of Ellington’s “Squeeze Me, But Please Don’t Tease Me” together. His full-bodied tone filled the intimate space with a warm vibrating glow, the effervescence of his sound soaring over the big band, spraying us with showers of light. As I stood next to him, I felt a heart/mind meld.

The power of Terry’s swinging, a quality Albert Murray called the “velocity of celebration,” along with his swift doodle-tonguing runs, felt like magic carpet rides of brilliance. His mastery joined strength with mercy, and power with compassionate understanding.

Those shared musical tones and moments with Clark Terry were, for me, direct transmission of jazz essence. His state of flow entrained me; my awareness of music and sound forever transformed. My saxophone playing immediately improved. I gained the confidence to project my identity into the world, paving my transition to manhood as well as watering the soil of my own mastery quest and destiny as a bridge to jazz and blues idiom wisdom.

Me, Clark Terry, Donald Cantwell, and a ringer trombonist from the Eastman Music School

I entered the chapel like a caterpillar, I left it a butterfly, having been nurtured on the everlasting Ambrosia, the nectar of jazz. Thanks, Clark, for changing not only my life for the better, but for doing the same for millions of others on record, in person, and in private sessions of lessons with a grand master.

My love for jazz has endured, but I maintain a beginner’s mind of curious passion, flame lit, the wick of romance sparked those many years ago still burning bright.

My early romance with jazz taught me life lessons in small doses of sonic insight. I became ready in advance for the love, pain, hope and inevitable regrets of life’s journey. She prepared me for the ups, downs, and all-arounds.

The Stage Band in high school and the Big Band in college also taught me about human style and personality.

The trombone section, between the trumpets and saxes, is a peacekeeper, making sure we all get along, replenishing and nourishing like water.

The trumpets, brassy and bold, fiery but with warmth beneath bravado.

The saxophones, in a friendly contest with the trombones for title of most-like-the-human-voice, blows through obstacles with force of wind and spirit. Like air.

The rhythm section, as earth, keeps time, life’s rhythm

Whether high, low, rough, or billowy

the rhythm section grounds,

chugging along . . . like a train

quintessential groove

swing and syncopation

keeps on keepin’ on

straight ahead.

Thanks to CALM for commissioning my audio story, “For the Love of Jazz,” from which this and my most previous post derived.

For the holidays, we’re happy to announce a special offer for a CALM subscription at a 40% discount. Go to Calm.com/jazz and enter the code word “jazz.”

Enjoy!