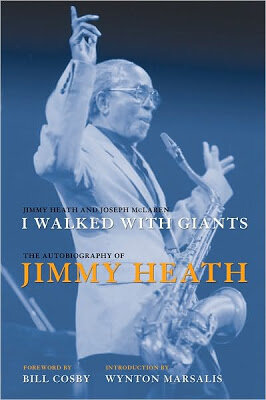

Jimmy Heath: A Jazz Titan Departs

Jimmy Heath

Jimmy Heath, a giant of jazz from its golden era, has departed, joining the ancestors. He was 93. Below, a few remembrances and his own words from an interview I had the privilege to do with him nine years ago.

Reminiscing on Jimmy

We last spoke in spring 2019 by phone. He sounded good, as he always did, though I knew his health was declining. I invited him to participate as a guest for a series on Improvisation I curated at Jazz at Lincoln Center. He reminded me that he wasn’t in Queens, that he was recuperating in Georgia. I thought of his beloved Mona, his sweet, gentle wife. I think of her now.

Though we didn’t speak again, I was honored that he was on our email list and opened and read many of the blog posts we’ve released since our launch last November.

In 1982 I remember buying an album in which the architectural logic and soulful flow of Mr. Heath’s improvisations caught my ear in a special way. Mad About Tadd, a tribute to one of bebop’s greatest composers, Tadd Dameron, was a showcase for the talents of Slide Hampton, Kenny Barron, Ron Carter, Art Taylor, and Jimmy. Back then, and occasionally now, when moved by album, or a particular song and jazz solos, I’ll listen, over and over, and practice their solo lines as a vocal scat.

For Mad About Tadd I learned each of Jimmy’s solos, and, in fact, listened to it on Sonos this past week with Jewel, smiling as the ensemble of masters under the group name Continuum brought back memories of the early days of my love affair with the music.

A few years later I took part in Jazzmobile classes in Harlem. Jimmy, called by Jazzmobile Director and Executive Producer Robin Bell-Stevens a co-founder of the organization, was already revered for his mastery on saxophone, his superlative arranging skills, his prowess as a composer, and his leadership of bands small to large. But one of the most lasting aspects of his legacy will be his work in jazz education, passing on his wealth of knowledge and experience to generations of young musicians.

At the end of the summer sessions, where I took classes with Charles Davis and Lisle Atkinson, I played a solo on alto sax in the student band and tried out a descending chromatic lick I learned from The Charlie Parker Omnibook. Mr. Heath was right there, spurring us on with that smile that could light up a room. I also recall seeing him at NEA Jazz Masters ceremonies at Jazz at Lincoln Center; he was honored with the award in 2003. That was around the time I began consulting for the National Jazz Museum in Harlem and helped organize and conduct interviews for their Harlem Speaks series. When I interviewed Antonio Hart, one of Jimmy’s most beloved Queens College protégés, Jimmy honored us all with his presence, beaming with a mentor’s pride. He even joined us on stage.

Antonio Hart, left; Jimmy Heath, right.

Conversing with Jimmy

But my proudest moment came from interviewing him nine years ago for a profile in the New York Daily News. His Philly homeboy Benny Golson was the other featured artist of the piece, which wove together their insights on jazz, creativity, and the compositional nature of improvisation.

Here are excerpts from that conversation, which began with a question on his plans for a six-day run at Dizzy’s Club Coca Cola. His responses are bolded.

I’m planning to play some original compositions, as always. And standards. I’m pulling out some originals that I haven’t played in a while, that people have been asking me for lately. “CTA” and some others of mine that we haven’t played in a long time.

I originally played it with the Miles Davis Sextet; he recorded it in 1953, with J.J. Johnson and Art Blakey. Some of my colleagues, some of the giants I’ve worked with.

“A Sound for Sore Ears” is one that I’m playing from a larger work I wrote for Joe Henderson called Harmonic Future. And I’m pulling out “Gemini” and “Gingerbread Boy” that were recorded by Miles and Cannonball Adderley, Dexter Gordon, and people like that.

How do you relate the role of the jazz composer as compared to European classical composers? And how many long works have you written?

Jazz composers generally use more syncopated rhythms than in classical music since it comes from the African end of the music.

I’ve written approximately 15 longer works, which are a little more involved, with different grooves that have presented themselves over the years in our music. A little Latino influence, a little contemporary influence, swing, the whole experience of my life. It’s not closed to any genre; I just try to write the best I can in that particular style.

Improvisation?

That is spontaneous composing. You’re standing on your feet, and you’re composing with a given structure—or not, free. The good improvisers will always have a pattern that they’ll repeat in different strata of the harmony. If you listen to people who are also writers, the way they play a solo is like they’re composing as they go along.

What’s your composing process?

It’s always different. Sometimes you can compose from a rhythmic pattern, or you can compose from the rhythm of the lyrics. You can compose from intuition; you can compose from a harmonic structure, from the piano. You can compose from your instrument, in my case the saxophone. There are four or five ways that compositions pop in your head. You work them out if you have the knowledge to develop them on the piano.

“Gingerbread Boy” was just a melody I came up with, but the title was because of my inter-racial marriage. A friend of mine from Philadelphia named Jimmy Oliver, a saxophonist who ‘Trane, Benny Golson and I used to hear said to my wife, when she was pregnant, “Oh, you’re going to have a gingerbread boy.” Because she happens to be Caucasian and I’m an African-American.

I do a lot of compositions for people I admire. “Gemini” is for my daughter, who’s a Gemini. The one I did for my brother Tootie is called “Two Tees.” I did one for Percy called “Big P.”

The Heath Brothers: Percy, Jimmy, and Albert (“Tootie”)

I did one for Miles Davis called “Miles and Miles” that Chet Baker recorded, and Art Blakey [too]. They’re usually all for someone I admire. Like “Smiling Billy” for Billy Higgins, who smiled when he played, and he made everybody else smile! “Moody’s Groove” for James Moody. That’s one that I wrote the lyric to. I recently re-arranged “Mona’s Mood”—that’s for my wife, originally from 1960. Duke and all the great composers, they would go back over a period of time, and take that same composition and re-work it. Because you’re not satisfied with the same way it’s done all the time. So you re-do it.

Who are your favorite composers?

From the bebop generation, Tadd Dameron and Kenny Dorham were the romantics. Their love songs seemed to affect me as did the Broadway writers and the Western classical writers, as with Tchaikovsky, whose “Romeo and Juliet” someone wrote lyrics to and called it “Our Love.” I like people like Ravel and Debussy, in terms of romantic writers.

Among those who wrote bebop lines, number one would be Charlie Parker. A super composer. Sonny Rollins is another good composer in the bebop vein and in the Calypso style. Benny Golson is a great writer, my homeboy. The tribute to Clifford Brown, “I Remember Clifford,” is a beautiful composition; it doesn’t get much better than that, you know what I’m sayin’? He wrote songs that are interesting harmonically—“Stablemates” and “Whisper Not.” Benny’s a very passionate person and a very spiritual person also. He used to play piano in church and all.

John Coltrane wrote one of the most beautiful songs in the history of music, “Naima.” That song has a spiritual quality that is equal to any, to me.

Duke and Strayhorn are the #1 masters in our idiom. You can’t categorize them—as Duke would often say about others, they’re “beyond category.” There’s hardly a recording I make that I don’t do an Ellington or a Strayhorn composition. I still play songs like “Warm Valley,” “Passion Flower,” “Sophisticated Lady.” I also did a big band arrangement of “A Flower is a Lovesome Thing.”

In the coming days, weeks, years and decades, when the full measure of Jimmy Heath’s contribution to the jazz idiom, and therefore to American culture, is considered, he won’t be called “Little Bird.” Jimmy Heath will be remembered, as his music is played around the world from now into perpetuity, as a Jazz Titan and Grandmaster. But he was also down to earth. During public shows, he’d speak from the stage, and do a little impromptu call-and-response, with the black American vernacular version of the word “alright.”

Aii-ight?, he’d ask. Aii-ight, Mr. Heath. Thank you for being and becoming your best as a musician, husband, brother, father, and friend to so many.

We love you madly.