Capacity for Caring and Instruments for Change

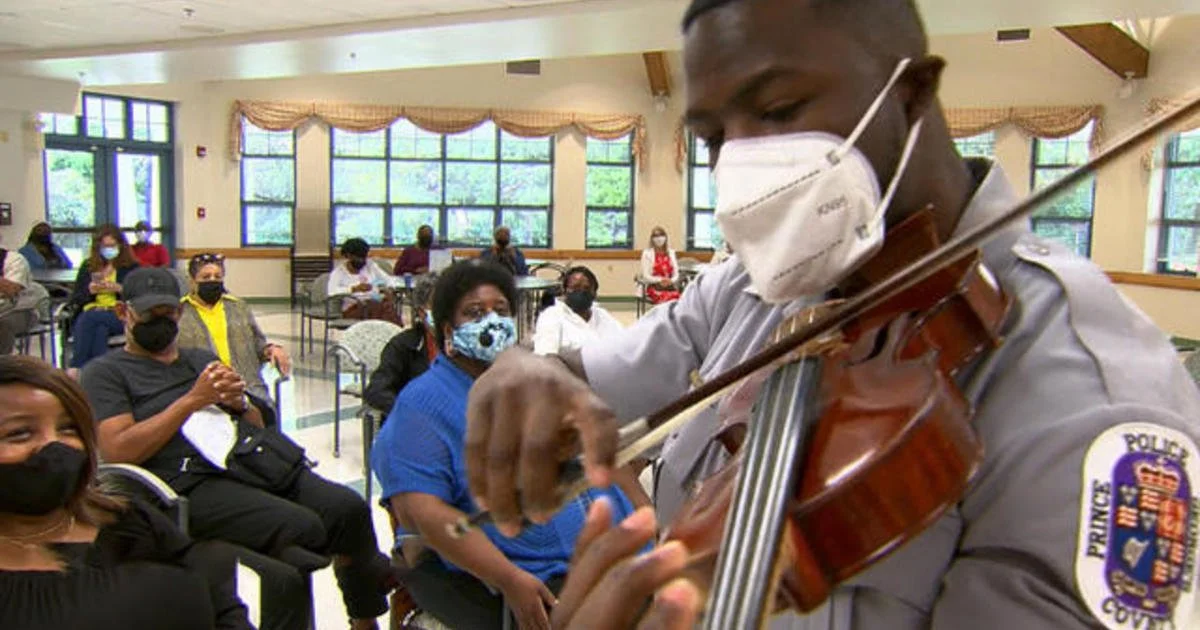

Police Officer Strachan playing for community residents

An Instrument for Caring

I write this post on Veterans Day—a day of remembrance and gratitude for those who died in service to this country. On CBS Mornings, a young staff sergeant who was preparing to be a part of the honor guard for the unknown soldier ceremony was told by a comrade: “The reason you’re nervous is because you care.”

Caring can make us nervous because, in our desire to do well, we are vulnerable. How will our effort be received, particularly if things don’t go as we planned? Beyond that immediate intention to do good, expressing care feeds our soul. Our capacity for care can be profoundly deep, particularly in those moments when there is no immediate reward. Yet, neuroscience tells us that our brain recognizes these acts as a reward, and hence, the feel-good chemical dopamine begins to flow.

Alexander Strachan is a beautiful example of deep caring and the shapeshifting possibilities I wrote about in a recent post. Studying the violin since he was a teen, Strachan started playing for seniors in hospice. When COVID took away performance opportunities, he shifted from being a classical violinist to a Prince Georgia’s County, Maryland police officer. Now he does both, but he doesn’t feel that there is a disconnect in carrying both a violin and a weapon, while playing in his uniform, because, as he says, “you can be unique” in how you show up to serve your community.

Strachan holds space for both roles because he says that the song notes unlock powerful memories, impacting seniors positively. The sometimes “gritty” moments of death he experiences while playing also serves him in his police work. Strachan uses his violin as his instrument of caring—managing a wonderful balance of feminine and masculine energies so people can see a different sides of him.

Responsibility & Generosity = Caring

Some months back, life for residents of Waverly, Tennessee was devastated by flooding after seventeen inches of rain in several hours. Lives were lost, property damaged beyond repair, and the local high school band lost all their instruments to the rising water. Grammy winning country singer Vince Gill felt compelled to help the music students: he donated $100,000 worth of band instruments.

Gill asks a fundamental question: “Why can’t we be like this all the time?”

Seeing & Recognizing = Caring

The Zulu greeting Sawubona means: I see you. The essence of the greeting recognizes the person and bears witness to their experience and journey.

Esperanza Spalding is a four-time Grammy winner and jazz bassist extraordinaire. A Harvard professor, Spalding turned her focus to jazz icon Wayne Shorter—her hero and mentor. The 88-years-old saxophonist and composer had long dreamt about composing an opera, but with his health fading, Spalding was concerned that it just wouldn’t happen.

So Spalding took a year off from Harvard, and wrote the libretto to Shorter’s music, bringing their production of the Greek myth “Iphigenia” to the stage. It was unfathomable to Spalding that Shorter’s dream, eight years in the planning, would not be made manifest. It was important for Spalding to see the project through.

It’s not a coincidence that all three instances are music-related—music is a powerful connector. Whether it’s musical instruments or self-as-instrument, Strachan, Spalding, and Gill demonstrate generative mindsets that ask what I can give instead of what I can get.