Bass Reeves: An Unsung Hero Gets His Due

. . . isn’t one of the implicit functions of the American frontier to encourage the individual to a kind of dreamy wakefulness, a state in which he makes—in all ignorance of the accepted limitations of the possible—rash efforts, quixotic gestures, hopeful testings of the complexity of the known and the given?

—Ralph Ellison

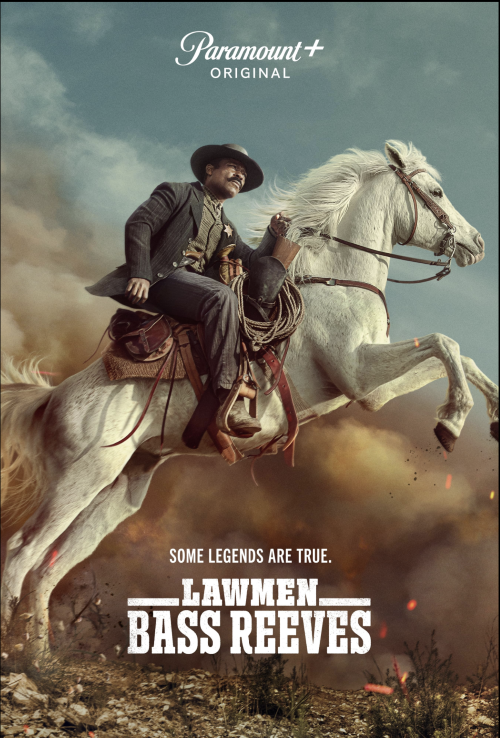

The hero archetype is so universal across human cultures that Joseph Campbell borrowed a phrase originated by James Joyce and called the hero’s tale the monomyth. Bass Reeves, depicted above by actor David Oyewolo, was a real-life hero of frontier America, a man born enslaved in Arkansas who became a legendary lawman in a land—before Oklahoma became a state—that was called Indian Territory.

In Myth: A Biography of Belief, David Leeming relates the “universal hero myth that speaks to us all and addresses our common need to move forward as individuals and as a species.” Then he quotes Campbell from The Hero With a Thousand Faces:

The Hero is the man or woman who has been able to battle past his personal and local historical limitations to the generally valid, normal human forms.

Leeming completes Campbell’s basic formulation: “The essential characteristic of this archetype is the giving of life to something bigger than itself. By definition, the true hero does not merely stand for the status quo; he or she breaks new ground.”

Bass Reeves’ heroic journey began by escaping enslavement and becoming a fugitive from injustice. Albert Murray provides insight into the heroic nature of such figures in The Omni-Americans:

The fugitive slave, for instance, was culturally speaking certainly an American, and a magnificent one at that. His basic urge to escape was, of course, only human—as was his willingness to risk the odds; but the tactics he employed as well as the objectives he was seeking were American not African. . . Given the differences in circumstances, equipment, and, above all, motives, the legendary exploits of white U.S. backwoodsmen, keelboatmen, and prairie schoonermen, for example, became relatively safe when one sets them beside the breathtaking escapes of the fugitive slave beating his way south to Florida, west to the Indians, and north to far away Canada through swamp and town alike seeking freedom—nobody was chasing Daniel Boone!

—Albert Murray

Bass Reeves, July 1838 – January 12, 1910

After escaping involuntary servitude, Reeves beat his way west and took refuge with the Seminole, Cherokee, and Creek Indians. He learned their customs, tracking skills, and several Native American languages. He also became an expert sharpshooter. When he was legally freed via Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, he returned to Arkansas, becoming a farmer and rancher, and marrying Nellie Jennie from Texas. They had ten children.

Then came another call to adventure: Indian territory didn’t have federal or state jurisdiction yet, so outlaws, thieves, and murderers took refuge there. Judge Isaac Parker of the Federal Western District Court appointed U.S. Marshal James F. Fagan as head of several hundred deputies. Fagan heard of Reeves’ vast knowledge of the area and language skills, so he recruited him as a U.S. Deputy Marshal to help clean up the territory and bring in the outlaws—dead or alive.

Bass Reeves served in that capacity for 35 years, sweeping up 3000 outlaws in a period where over a hundred of his fellow deputies were killed. During his service, he killed 14 men and was quoted as saying that he only did so in the discharge of his duty and to save his own life.

Upon his death in 1913 in Muskogee, Oklahoma, the local newspaper declared that “Everybody who came in contact with the Negro deputy in an official capacity had a great deal of respect for him and at the courthouse in Muskogee one can hear stories of his devotion to duty, his unflinching courage, and his many thrilling experiences . . .” (For historical accounts of such experiences, check out this story.)

Championing Excellence

Rumor has it that Reeves was the basis of the radio and television series, “The Lone Ranger.” If you recall hearing the name Bass Reeves in the past few years, it’s likely because Colman Domingo portrayed him in the television series Timeless (2017), as did Delroy Lindo in the 2021 feature film, The Harder They Fall. He also served as the primary inspiration for Will Reeves in HBO’s latest Watchman adaptation in 2019.

But the most significant recognition of Reeves’ legacy is the eight-episode Lawmen: Bass Reeves, currently running on Paramount+. The actor David Oyewolo (The Butler, Selma) endeavored for eight years to bring this story to the small screen; he also serves as an executive producer.

In an excellent segment on CBS Sunday Morning, Oyewolo explained why he chose to fight to bring Bass Reeves’ story to television and answered a lingering question: Why isn’t Bass Reeves better known as an American hero?

“A tenet I live my life by is ‘Excellence is the best weapon against prejudice’. [Reeves] was excellent. It was difficult to say, ‘Oh, that’s just a black man, who is unworthy, who should be subjugated.’ You couldn’t dismiss him in that way.

“That’s also the reason: to not celebrate him is wrong.”

Outchorus

Bass Reeves broke new ground in the American mythosphere, battling past his personal limits and the social and racial restrictions of his time. He was born victimized but refused to remain a victim in perpetuity. Through what Ellison in the introduction to Shadow and Act called “hopeful testings of the complexity of the known and the given,” Reeves’s extraordinary achievement expands the frontiers of our imagination beyond the decoy of race into true American heroism.

Coda

Excellence as a tool in the fight against bigotry is one of several themes in the last episode of Straight Ahead: The Omni-American Podcast, featuring economist and public intellectual Glenn Loury. To watch, click the image above.